2015 working paper from Harvard University Law School on the expanded corporate use of the First Amendment over time, based on a statistical analysis of 423 cases.

by Leighton Walter Kille | March 26, 2015 | judiciary, law

You are free to republish this piece both online and in print, and we encourage you to do so with the embed code provided below. We only ask that you follow a few basic guidelines.

by Leighton Walter Kille, The Journalist's Resource

March 26, 2015

The 2010 Supreme Court case Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission has been portrayed by supporters and critics alike as a watershed in the history of campaign finance and free speech in the United States. The decision explicitly freed corporations to spend unlimited sums on “electioneering communication” intended to help elect or defeat specific candidates. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the majority, wrote that the ruling would enable political speech that is “central to the First Amendment’s meaning and purpose.” In his dissent, Justice John Paul Stevens argued that the ruling would allow wealthy corporations to “unfairly influence” the electoral process by marginalizing the speech of less-powerful individuals and groups.

Whatever one’s position on Citizens United, there is no question that its impact has been substantial: The Center for Responsive Politics indicated that super PACs created in the wake of the ruling spent more than $600 million during the 2012 election cycle. Research from the National Conference of State Legislators in 2011 indicated that 24 states had laws affected by the ruling — ones that banned political activity by unions, corporations or both. A 2014 report from the Brennan Center for Justice of New York State University, “After Citizen United: The Story of the States,” explores the impact that case has had in state and local elections.

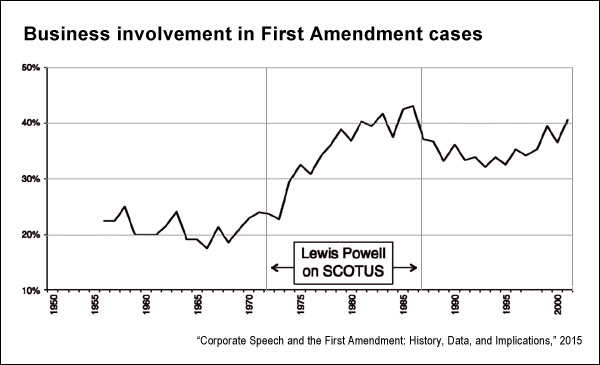

A 2015 working paper from Harvard Law School, “Corporate Speech and the First Amendment: History, Data and Implications,” indicates that Citizens United, while certainly important, is only the latest in a series of cases that have expanded corporate use of the First Amendment. In his research, the author, John C. Coates IV, performed an analysis of nearly 13,000 Supreme Court decisions from 1946 to December 2014. Of these, 423 were selected that involved freedom of speech, press or assembly covered by the First Amendment. Cases were coded according to the nature of the plaintiff — companies, individuals, government entities, or others — and which party won. “Victories were distinguished between those in which a party defeated an attempt to persuade the Court to strike down a law or regulation under the First Amendment and those in which a party succeeded in so persuading a Court to strike down a law or regulation,” Coates writes.

The study’s key findings include:

“These findings present a challenge to the view, articulated by the majority and concurrences in Citizens United and Hobby Lobby, that corporations and other business entities should be understood ‘simply’ as aggregations or associations of individuals, and so should not be distinguished from them for purposes of First Amendment analysis,” the author writes in his conclusion, continuing: “The corporate takeover of the First Amendment represents a pure redistribution of power over law with no efficiency gain — ‘rent seeking’ in economic jargon. That power is taken from ordinary individuals with identities and interests as voters, owners and employees, and transferred to corporate bureaucrats pursuing narrowly framed goals with other people’s money. This is as radical a break from Anglo-American business and legal traditions as one could find in U.S. history.”

Related research: A 2014 study published in Perspectives on Politics, “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens,” analyzes the relative influence of political actors on policymaking. The researchers sought to better understand the impact of elites, interest groups and voters on the passing of public policies. The authors, Martin Gilens of Princeton and Benjamin Page of Northwestern University, found that compared to economic elites, average voters have a low to nonexistent influence on public policies. “Not only do ordinary citizens not have uniquely substantial power over policy decisions, they have little or no independent influence on policy at all.” In cases where citizens obtained their desired policy outcome, it was in fact due to the influence of elites rather than the citizens themselves.

Keywords: First Amendment, corporations, Court of Appeals, Virginia Pharmacy, Bellotti, Central Hudson, Citizens United, Hobby Lobby, lobbying, rent-seeking